Not all things are built to obey…

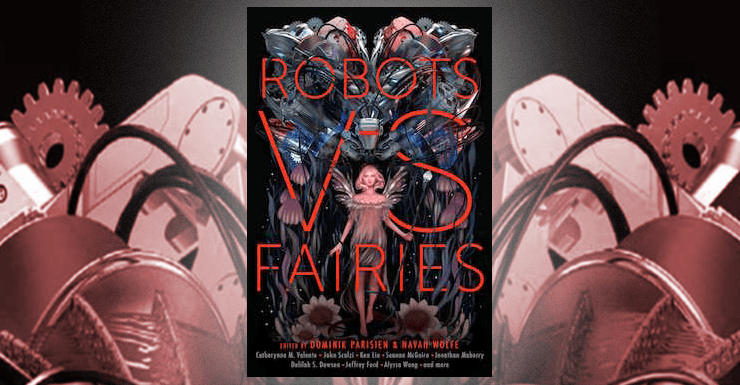

We’re thrilled to share Sarah Gailey’s “Bread and Milk and Salt,” originally published in Robots Vs. Fairies (Saga Press, 2018).

The first time I met the boy, I was a duck.

He was throwing bread to other ducks, although they were proper ducks, stupid and single-minded. He was throwing bread to them on the grass and not looking at the man and the woman who were arguing a few feet away. His hair was fine and there were shadows beneath his eyes and he wore a puffy little jacket that was too heavy for the season, and the tip of his nose was red and his cheeks were wet and I wanted him for myself.

I waddled over to him, picked up a piece of bread in my beak, and did a dance. I was considering luring him away and replacing his heart with a mushroom, and then sending him back to his parents so they could see the rot blossom in him. He laughed at my duck-dance, and I did an improbable cartwheel for him, hoping he would toddle toward me. If I got him close enough to the edge of the duck pond, I could pull him under the water and drown him and weave mosses into his hair.

But he didn’t follow. He stood there, near the still-shouting man and the silent, shivering woman, and he watched me, and he kept throwing bread even as I slid under the surface of the water. I waited, but no little face appeared at the edge of the pond to see where I had gone; no chubby fingers broke the surface tension.

When I poked my head out from under a lily pad, the proper ducks were shoving their beaks into the grass to get the last of the bread, and the man and the boy were gone, and the woman was sitting in the grass with her arms wrapped around her knees and a hollowed-out kind of face. I would have taken her, but there wouldn’t have been any sport in it. She was desperate to be taken, to vanish under the water and breathe deeply until silt settled in the bottoms of her lungs.

Besides. I wanted the boy.

Buy the Book

Robots vs. Fairies

The next time I met the boy, I was a cat.

To say that I “met” him is perhaps misleading, as it implies that I was not waiting outside of his window. It implies that I had not followed his hollowed-out mother home and waited outside of his window every night for a year. It is perhaps dishonest to say that I “met” the boy that night.

I am perhaps dishonest.

He set a bowl of milk on his windowsill. I still don’t know if he did it because he’d spotted me lurking, or if he did it because he’d heard that milk is a good gift for the faerie folk. Do children still hear those things? It doesn’t matter. I was a cat, a spotted cat with a long tail and bulbous green eyes, and he put out milk for me.

I leapt onto his windowsill next to the precariously-balanced, brimming bowl, and I lapped at the milk while he watched. His eyes were bright and curious, and I considered filling his eye sockets with gold so that his parents would have to chisel through his skull in order to pay off their house.

I peered into his bedroom. There was a narrow bed, rumpled, and there were socks on the floor. A row of jars sat on his desk, each one a prison for a different jewel-bright beetle. They scrabbled at the sides of the glass. The boy followed the direction of my gaze. “That’s my collection,” he whispered.

I watched as one beetle attempted to scale the side of her jar; she overbalanced, toppled onto her back. Her legs waved in the air, searching for purchase and finding none. The boy smiled.

“I like them,” he said. “They’re so cool.”

I looked away from the beetles, staring at the boy in his bedroom with his narrow bed and his socks. I ignored the sounds of beetles crying out for freedom and grass and decaying things and air. They scratched at their glass, and I drank milk, and the boy watched me.

“My name’s Peter,” the boy said. “What’s yours?”

“It doesn’t matter,” I lied, and he did not look surprised that I had spoken.

He reached out tentative fingers to touch my fur. A static spark leapt between us and he started, knocking the bowl of milk over. It clattered, splashed milk as high as his knees. Somewhere deep inside the house, the woman’s voice called out, and the creak of her barefooted tread moved toward his bedroom.

“You have to go,” he whispered, his voice urgent. “Please.”

“Okay,” I said. He stared at me as the rumble came closer. “Good luck, Peter.”

I leapt down into the dark garden as his bedroom door opened and listened to their voices. She spoke to him softly, and he answered in whispers. I didn’t leave until her hand emerged, white as dandelion fluff in the moonlight, and pulled his window shut.

The third time I met the boy, I was a deer.

I’d wandered. I wasn’t made to linger, and it hurt my soul to wait for him. I amused myself elsewhere. I turned into a woman and led a little girl into the woods to find strawberries, and left her there for a day and a night before sending her back with red-stained cheeks and a dress made of lichen. I was a mouse in a cobbler’s house for a month, thinning the soles of every shoe he made until he started using iron nails and I had to leave. As a moth, I whispered into the ear of a banker while he slept, and when he woke, he was holding his wife’s kidney in his clenched fist.

Small diversions.

I was a deer the night I came back for him. White, dappled with brown, to catch his attention. I wanted him to climb out of his window and follow me into the hills. I wanted to plant marigolds in his mouth and sew his eyes shut with thread made from spider’s silk. I wandered up to his window, and it was open, and there was a salt rock there.

Clever boy. He’d been reading up. I licked at the rock with a forked pink tongue.

“Is that what your real tongue looks like?” he murmured from behind me. I jumped. I hadn’t expected to see him outside, and he’d crept up so quietly.

“No,” I said. “It’s just how I like it to look when I’m a deer. When did you get so tall?”

“What do you really look like?” he asked.

I flicked my tongue at the salt rock again. “What do you really look like?” I asked.

Peter cocked his head at me like a crow. “I look like this,” he said, gesturing to himself. I snorted.

“I’ve been waiting for you for so long. Years,” he said. “I almost thought I made you up.” I looked up at him and my eyes iridesced in the moonlight and he stared.

“Come with me,” I said.

“Show me what you’re really like,” he said.

I shoved my wet black deer-nose into his palm. He hesitated, then ran his hand across my head. My fur was as soft as butter that night. He caressed my face, brushed the underside of my chin. I turned my face into his hand and breathed in the smell of his skin, his pulse. I closed my teeth around the pad of flesh at the base of his thumb and sank them in, biting down deep and hard and fast.

“What the fuck—” he cried out, but before he could pull his hand away, I flicked my tongue out and tasted his blood.

“That’s what I’m really like,” I said, my voice low and rough. He swallowed, his Adam’s apple bobbing, and I licked his blood from my muzzle. It burned going down—iron—but it was enough to bind us. He would run from me, but he would never be able to escape me altogether. Not now.

He cradled his hand against his chest.

“I have to go,” he whispered.

I watched him walk inside, and I felt the burning in my belly, and I knew that he was mine.

Every time I came back to the boy Peter, he was a little different. When I was a toad drinking milk out of a saucer in his palm, he had hair on his chin and a pimple on his nose. When I was a dove pecking at breadcrumbs on his bedside table, he was a twitchy, stretched-out thing, eyeing the door and wiping sweat from his palms. When I was a kangaroo-mouse nibbling at rock salt on the hood of his car, he was a weaving drunk in a black suit with tears streaming down his face.

“It’s my house now, you know,” he said as he walked from the car to the front door. “The old bastard’s dead. You can come inside, and you don’t have to hide or anything.” He held the door open, leaning against the frame, staring down at me.

“You don’t have to live there,” I said. “You could come with me. I know a place in the forest where there’s a bed made from soft mosses and a bower made from dew. You could come with me and live there and eat berries that will make you immortal.” His vertebrae would hang from the tree branches like wind chimes, and the caterpillars would string their cocoons from his ribs in the summertime. “Come with me.”

“Tell me what you are.”

“Come with me.”

“Show me what you really look like,” he said.

“Come with me, and I will,” I replied.

He looked at me for a long time, and then he took a step toward me, and I was sure that he was going to follow me. But then he leaned over and vomited onto the front porch of the house that was now his, and then the door slammed in my face, and I was left outside with my salt.

“You can take any form you want, right?”

His fingertip traced patterns in the milk that was spilled across his kitchen counter. I was a huge snake, black with a rainbow sheen across my scales like oil on water.

“I suppose so,” I replied, sliding through a puddle on my belly. I was getting fat and slow on the boy’s bribes. He held his fingers out and passively stroked my back as I slipped past.

“Why aren’t you ever a person?” he asked.

“What kind of a person would I be?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “Like . . . a person. A regular person.”

“Like this?” I took the form of his mother, and he flinched. Then I took the form of a woman I’d known once, a woman who had also left out bread and milk and salt. Bright eyes and big curls and a body like honeyed wine. I flicked a forked tongue at him, my deer-tongue, and his answering laugh was strange.

“Yes, like that. Just like that.” He laughed that strange laugh again, and I turned back into a snake. “Why don’t you ever look like yourself?” he asked.

“Why don’t you?” I answered. He rested his hand in my path, and I slid over it. He frowned.

“I do look like myself, though,” he said. “I look like myself all the time.”

“So do I,” I said. He shook his head.

“No,” he said. “I’ve been researching you. Did you know that? I’ve been reading, and I know what you are now. I know what you look like.”

“Do you now?” I drawled. His hands were warm under my belly and I was sleepy from the milk and the heat. He moved me, set me down. Paper rasped beneath me.

“You look like that,” he whispered. The page he’d set me upon featured a watercolor of a child with butterfly wings and fat, smiling cheeks. She was sitting on a red and white toadstool.

“Aha,” I said, curling into coils. “Aren’t you clever.”

“You can show me,” he said. “I’m a safe person for you to show. I promise.”

He traced my coils with a fingertip, and I curled them tight-tight-tighter, until I was no bigger than the toadstool in the drawing. But I couldn’t make my snake-self smaller than his fingertip.

“Come inside,” he said.

It had been two years. I had stayed away long enough to forget the reasons I was staying away. My memory is a short one, and he had been putting out bread, and milk, and salt, and the smell of them was so strong, and I was so hungry. And my belly still ached where his blood had seared me.

I was bound. And I am what I am. So I followed.

“I have something to show you,” he said. “It’s the culmination of my work.” He led me into his childhood bedroom—the same desk was there, but instead of jars, it was taken up by a large glass tank and an elaborate maze. I was a chinchilla that day, too big for the maze, the right size for the tank. I perched on his hand and nibbled at a bread crust and looked with noctilucent green eyes.

“Watch,” he said, and he reached into the tank with the hand that wasn’t holding me. When he opened his palm in front of my eyes, a large brown cockroach straddled his life line, its antennae waving.

“You’re still . . . collecting?” I asked, watching the cockroach smell the air. She almost certainly smelled me. Chinchilla-me, and the real me underneath.

“Oh, yes,” he replied. “Well. Yes and no. This is part of my research.”

The cockroach took a tentative step forward. Peter tipped his hand toward the maze, and the roach fell in.

“Watch,” Peter said again, moving me to his shoulder. I looked into his ear—he’d started growing a few hairs in there.

“You’re so strange,” I said, and his cheek plumped as he grinned.

“Watch,” he whispered a final time, so I watched.

He picked up a little cube from the corner of the desk and began twiddling his thumbs over the top of it. As he did, the cockroach spun in a slow, deliberate circle. “Do you see?” he said, and I didn’t see, so he showed me. He slid his thumbs across the top of the cube, and the cockroach navigated the maze with all the speed and accuracy of—

“A robot?” I asked. It was a word I’d heard several times from several people over the years I’d been gone; a word the boy Peter had used when he whispered to me about his secrets and dreams.

“Not quite,” he said, swallowing a laugh.

“I don’t understand.” I finished my bread and licked my fingers clean.

“I installed receivers in her rear brain,” he said. “I can control where she goes.” He turned and looked at me, so close that he was mostly eye. “How many brains do you have?”

I started to jump from his shoulder, but his hand was there in my way. “I’d like to go now,” I said.

“Why? Did I say something wrong?”

His hand was in my way, no matter where I turned. Unless I turned toward his face, and then his mouth loomed close, too close. “I just . . . I need to go,” I said. “Please let me go.”

“Tell me why,” he demanded. “I can’t fix it if I don’t know what I did.”

I turned into the woman, making myself too heavy for his shoulder to support. He fell backwards and I leapt up, standing over him. “You turned that creature into a toy,” I said.

“So what?” he asked, still sitting on the floor, staring up at me with his mouth half open. Staring at my skin. “How is that different from what you do?” I didn’t know how to answer, and he took my silence as an answer. “That’s right,” he said, a slow smile spreading across his face. “I’ve been reading. All these years. I know what your kind does. You turn people into toys, don’t you? Why is that better than me steering a stupid bug around?”

I took a step away from him, toward the window. It was closed, but I could open it with my human hands and then jump out of it as a rabbit or a sparrow. “It’s different,” I said. “I don’t turn humans into toys. I just let them do what they already wanted to do. You’re—you don’t even know what you are!” My voice was shaking. I rested a hand on the windowsill and then flinched away as my skin sizzled. I looked down—the sill was an inch-deep with iron shavings.

“What am I, then?” He stood up and moved towards me. “What am I?”

I changed, a different form with every breath. Him as a little boy. Him on the cusp of manhood. Him on the night of his father’s funeral. Him now. “You claim to be you,” I spat. “Just you. But what are you? Are you a fat little boy whose parents don’t love him enough to stop fighting? Or are you a youth who can’t escape home? Or are you a man whose father died before you could make him love you—”

I was still in his shape, speaking with his voice, when he slapped me hard across the mouth, knocking me-him to the floor. My head struck the corner of his desk, rattling the maze and the roach inside of it, and I saw stars, and I lost control.

I lost control.

“Oh my god,” he whispered. I blinked hard and realized my mistake.

I was me.

No disguises, no glamours, no fur or scales or feathers. Just me. Nothing like the little watercolor girl sitting on the toadstool. Wings, yes, but not like a butterfly’s wings at all. More like . . . leaves, I suppose. Like leaves when the beetles have been at them, but beautiful. Fine-veined and translucent and shimmering even in the low light of his house. Strong, supple, quick. Flashing.

I am thankful for the pain that brightened the inside of my head in the moments after I fell, because it dampens the memory. His hand on the back of my neck. His knee at the base of my spine. His fists at the place where my wings met my shoulders.

The noise they made when he tore them off.

I tried to change my shape to protect myself. When I wasn’t in my true form, my wings were hidden, and in that terrible moment when his weight was on top of me and the tearing hadn’t begun I thought that maybe I could escape by shifting. I went back to the woman-shape, because it was what I had most recently been before I was him, and it was all wrong, and it hurt, and my wings hurt—

And then he was laughing.

“I didn’t think,” he said, panting with exertion, “that it would be so easy.”

I screamed.

“They’re beautiful,” he said. He shook my wings—my beautiful, strong wings—and braced a hand on the desk to pull himself to his feet.

I screamed.

“Wow,” he breathed, running his fingertips over the delicate frills at the top of one wing. “Just . . . wow.”

I screamed.

He put my wings into a cabinet with an iron door, and he locked the iron door and wore the iron key around his throat.

The first night, I stayed on the floor of the maze-room, and I screamed.

The second night, I slept. The pain was unbearable. When I woke, I screamed.

The third night, my voice was gone, and I tried to kill him.

“Would you like some clothes?” he asked, his hand gripping my woman-wrist so tightly that I felt the flesh threatening to break. I tried to change—tried to become a mouse, or a viper, or a spider, anything—but I couldn’t. My wings were there—right there in front of him, on the table where he’d been studying them. But they were dead things. I would never get them back, and I’d never again have access to the power within them.

My magic was gone. I couldn’t change myself. The knife I had stolen from his kitchen fell from my hand, clattering to the floor near his feet.

“Death first,” I spat.

“What’s the problem?” he asked. “You were never using your wings anyway. You were always hiding them, pretending to be some kind of animal. Isn’t this what you wanted?”

He tossed me aside and I didn’t fall to the ground, because his bed was there. The cotton of his quilt was so soft against the skin of this woman-body I was stuck in. He stood a few feet away, considering me, and for the first time I wondered what precisely it was that he wanted me for.

“You might fit into some of my mother’s old things, if I still have them around,” he said. He walked out the door without a backwards glance, and I screamed into his pillows. Every time I inhaled, I breathed in the smell of his hair, and I had to scream again to rid myself of it.

I tried so many times, but everything I did was too obvious, and I was too weak. I tried to strangle him in his sleep, but my fingers were made for weaving arteries together into necklaces, and he woke before I interrupted his breath. I tried to poison him with a kiss, but it didn’t work.

“Well,” he said, his lips less than a breath away from mine, “I guess that’s another power you’ve lost.”

“No,” I said, “it’s impossible.”

“I’m not dead, am I?” he asked. He pushed me away, just a few inches, and he smiled. “Looks like you can kiss me all you’d like.”

He stared at my lips while he said it, and I lunged for him with my teeth bared. He shoved me away. “Maybe later,” he called over his shoulder. He walked through the door and locked it behind him, and I was trapped once more.

He didn’t need to lock the door, not strictly speaking. We were bound. Without my magic, I couldn’t have stretched the confines of that binding for more than a day.

I would always have to come back to him.

I slept in his bed. I lived as his wife. I did not enter his lab, with the maze and the cockroach and, from what he told me, the increasingly larger creatures. I did not touch the iron door of the cabinet that held my wings. I ate the bread and the milk and the salt that he brought to me, and I tried to kill him again and again and each time I failed.

He made me new wings out of metal and glass. He brought them to me and said that they’d be better than my old ones—more efficient. He said he’d been working through prototypes, and that these ones were ready for something called “beta testing.” He said the surgery to attach them would only take a day or so. I leapt at him and almost succeeded in clawing his eyes out.

It was nice to see the livid red wounds across his face for the week that followed. They healed slowly.

Not as slowly as the place on my back where my wings had been, of course. That took much longer—my skin was looking for an absent frame of bone and gossamer to hang itself on. The right side was a patchy web of scars by the time two months had passed, but the left bled and wept and oozed pus for another four before I realized the boy’s mistake.

Before I realized my opportunity.

I had taken to staring at myself in the mirror when he was gone. It was an oddity—before my magic was gone, I hadn’t been able to see myself in mirrors. Something to do with the silver in the backing, I’m sure. I had seen my reflection rippling in pools of water, and I had seen it bulbous and distorted in the fear-dilated pupils of thousands of humans—but never in mirrors. Never so flat and cold and perfect.

The day I realized Peter’s mistake, I was looking at my legs in the full-length mirror in his bedroom. My bedroom. He wanted me to call it “ours,” but I didn’t like the way the word felt in my mouth. I did like my woman-legs, although they were too long and too thick and only had the one joint. I liked the fine layer of down that covered them, and I liked the way the ankles could go in all kinds of directions. I liked the way the toes at the ends of my woman-feet could curl up tight like snails, or stretch out wide like pine needles.

I was looking at my woman-legs in the mirror, and I turned around to examine the way the flesh on the thighs dimpled, and my back caught my eye. It all fell together in my mind in an instant.

How could I have been so stupid? But, then again, how would I have known?

I twisted my neck around and reached with my short, single-jointed arms, and I couldn’t reach it. But I could see it in the mirror. The weeping, welted place where my left wing had been, the skin mottled with red. The sore on my shoulder, and the failing scars that attempted to form there.

And then, just a few inches below it: a lump beneath the skin, where a spur of wing remained.

It’s a good thing the woman-body made so much blood.

I didn’t want to go into the lab—I didn’t like the way all the creatures persisted in asking me to help them, didn’t like looking at them in their cages. Didn’t like seeing the sketches of my wings that covered the walls. Didn’t like seeing the attempts he’d made to re-create them with plastic and fiberglass.

But there were tools in the lab, steel tools, and I had the beginnings of a plan.

“Please,” a mouse with a rectangular lump under the skin of its back begged. “Please, it hurts, please.” Its nose twitched and it scrabbled at the sides of its cage like a beetle in a jar.

“I’ll do it if you tell me where he keeps the tools,” I answered.

The mouse stood on my woman-shoulder, the door to its cage hanging open, the voices of its fellows raised in a chorus of pain and fear and desperation. “In there,” it said, pointing its nose toward a tall cupboard with frosted glass doors. I opened the cupboard and saw that the mouse had spoken truly: rows of tools, metal and plastic and sharp and blunted and every one specific. I held the little creature in my hand and his heartbeat fluttered against my palm.

“Those are all the ones he uses when he puts the pain on our backs and makes us fly,” he whispered. “They’ll work for whatever you need. They’re worse than anything.”

“Is it frightening, when he makes you fly?” I asked.

I could feel the leap in his little mouse-chest. “Please,” he said.

“Of course,” I answered. I twisted my woman-wrist and snapped his neck, and his dying breath was a sigh of relief.

I dropped his body to the floor, where he landed with a soft paff. Then I thought better, and I picked him up, returning him to his cage and locking the door. His fellows huddled in the corners, burrowed into sawdust. They stayed far from the stench of his freedom.

I did it in the bathtub. I stopped up the drain so that I would know how much blood I’d lost, and I tied up the shower curtain so that it wouldn’t stain, and I reached behind myself with fists full of tools. A sharp tool, and a long tool, and a tool for grabbing, and a tool for burning. It wasn’t as hard as I had expected it to be—I had enough experience with pulling things out of humans, had nimble enough fingers.

I wouldn’t have expected the pain, but the boy Peter had ripped the other wing out without even using tools at all. So it really wasn’t so bad.

I reached into myself with the tool for grabbing as blood pooled around my feet. It was warm and soft and reminded me of more comfortable times, and I was thankful for it. I grit my teeth as I rooted around, cried out as the tips of the tool for grabbing found the spur. I clenched my fist, and I yelled a guttural, animal yell, and I pulled.

An eruption of white fire. A gout of burning blood spilling over my spine and buttocks. And there, right there in my hand, a two-inch long piece of wing. All that was left. Not bound behind iron, not hidden away in a collection.

Mine.

I wept with pain. I wept with relief. I wept with joy.

I did not let go of the tool, even as I unstopped the drain and ran water and washed myself, letting soap sting the wound in my back. I did not let it go as I dried myself. I did not let it go until it was time to bury it in the earth of the boy Peter’s weedy little flower garden. I had to force my fingers to straighten. I tucked the spur of wing into my cheek, sucking the woman-blood off of it, and buried the tool for grabbing with a whisper of thanks.

Before Peter came home, I walked back into his lab with my piece of wing poking at the soft flesh of my cheek. I opened the door and stood just inside, my hand resting on the doorknob.

Squeaks. Squeaks and chirps and even a high, steady scream from the rabbit.

“What are you saying?” I whispered, my voice wavering around the spur in my mouth. “What do you want?”

The squeaking intensified, rose to a fever pitch, and I smiled as the incomprehensible cacophony crashed over me.

I couldn’t understand a word they were saying.

It had worked.

“How’s your back doing?” The boy Peter asked that night as he climbed into his bed. Into my bed.

“Better, I think,” I answered, and my voice was almost normal. I had been practicing all day, learning how to speak around the piece of wing in my mouth.

“Good,” he said. He kissed me on my empty cheek, and then he rolled over and he closed his eyes and his breathing slowed and he was asleep.

He was asleep.

And I was awake.

I waited, waited, waited. I waited until he was deep asleep, so deep that a pinch on the plumpest part of his cheek wouldn’t wake him. And then I swung a leg over his hip, and I settled my weight onto the bones of his pelvis. I felt his hips underneath me and I waited for two breaths. If he woke up, I wouldn’t need to make an excuse. He would assume, and it would be over fast enough, and I could try again another night.

Two breaths.

He didn’t wake.

I toyed with the spur in my cheek. It was sharp at both ends, broad in the middle. Too big to swallow whole. I shifted it with my tongue until it was between my broad, flat-bottomed woman-teeth. I breathed in once, filling my mouth with the smell of old blood and wet bone, and then I bit down.

It tasted like me and like blood. It burned my tongue, and I bit down again and it burned my cheek. I chewed, chewed until it was a fiery paste, and then I swallowed, and I felt it. Underneath the lingering pain of the blood.

I felt the magic.

It flooded me, bright and brief as lightning, and there was so little time that I didn’t even have time to think, and I did it in that moment, and it was perfect.

I changed.

The boy Peter’s eyes flashed open. He looked at me, first through the veil of sleep and then through the veil of terror. I grinned down at him.

“What the fuck?!” He struggled to sit up, but I clenched my new thighs, pinning him. He wriggled, caught, and it wasn’t until I rested a thick-knuckled hand on his chest that he stilled. “What the fuck?” he whispered again.

“Yes, Peter,” I whispered back in my new voice. In his voice. “What the fuck.”

“But—how did you—you’re –“

“Don’t you like it?” I asked. I leaned down until our noses touched, and then I kissed him. He kept his eyes open, panic clenching his pupils. “Oh, come on, Peter,” I said, my lips moving against his so that he would feel his own voice humming across his teeth. “What’s the matter?”

“But—you can’t –“

“You’re right,” I said. “I can’t. Not anymore. That was the last time. That was the last of my magic.” I kissed him again, brushing his Peter-lips with my Peter-tongue, and he flinched violently away.

“Go away,” he said, but his voice was weak and I knew that he knew better.

“Never,” I whispered, and I rolled off of him. As I closed my eyes I smiled, because I knew that he would not sleep that night.

He might never sleep again.

I had never looked into mirrors before the boy Peter ripped my wings off.

Now, every morning was a mirror.

“Don’t look at me like that,” he said when he woke to find me perched on my side of the bed.

“Like what?” I asked. “Show me. What does my face look like right now?”

“Stop it,” he said when I climbed into the bathtub alongside him.

“Stop what?” I asked. “What am I doing?”

He hit me once, a closed fist and a slow, weak push of knuckles into my nose. It wouldn’t have hurt, but I leaned into him to make sure. He looked at his hand, and he looked at my face—at his own face—with blood coming out of it, and he whitened.

“I didn’t mean to –“ he started to say, and I wiped at the blood so that it smeared across my face.

“I didn’t mean to punch you,” I said. He bit his lip and I grinned. “I didn’t mean to make your nose bleed,” I continued in his voice, saying it the exact way I’d heard him say a thousand things. “I didn’t mean to hurt you like that. You just made me so mad.” I licked my lip where my blood was dripping, and the burn was worth it. “You made me so mad,” I said, “and I lost control.”

“Stop it,” the boy Peter said, and I laughed, and I kissed him, and when he shoved me away my blood was on his teeth.

He couldn’t look at me, but I wouldn’t let him look away. I would never let him look away. That night, with dried blood still flaking off my lips, I pressed my cheek to his. He flinched and tried to roll over.

“What’s wrong?” I whispered into his ear, my lips stirring his hair that was my hair that was his hair. “You wanted to see my true form, boy. Peter-boy.” He shook a little, maybe crying, and I grinned against his neck. “It’s only fair that you should see yours, too.”

I had not a scrap of magic left in me, it’s true. The boy Peter wept in our bed next to the perfect image of himself, who he could never escape, and from whom he could never look away—and it felt so good. It felt so perfect, to know that he would be constantly faced with the self that he had tried so hard to bury in accomplishments and explanations and excuses. In that moment, as I pressed my lips against his sob-clenched throat, I realized that there are more kinds of magic than the spark that had been stored in my little spur of bone and gossamer. That night he began a slow descent into darkness, and I felt a satisfaction deeper than that of a belly full of bread or a fistful of salt

“Goodnight, Peter,” I said. I let my head fall back onto my pillow, and that night, I slept the dreamless sleep of victory.

“Bread and Milk and Salt” © 2018 by Sarah Gailey

Reprinted from Robots vs. Fairies, edited by Dominik Parisien and Navah Wolfe.